Explore Bloomberg Tax's AI Lab.

Learn MoreOptimize Your Tax Process With Proven Tools

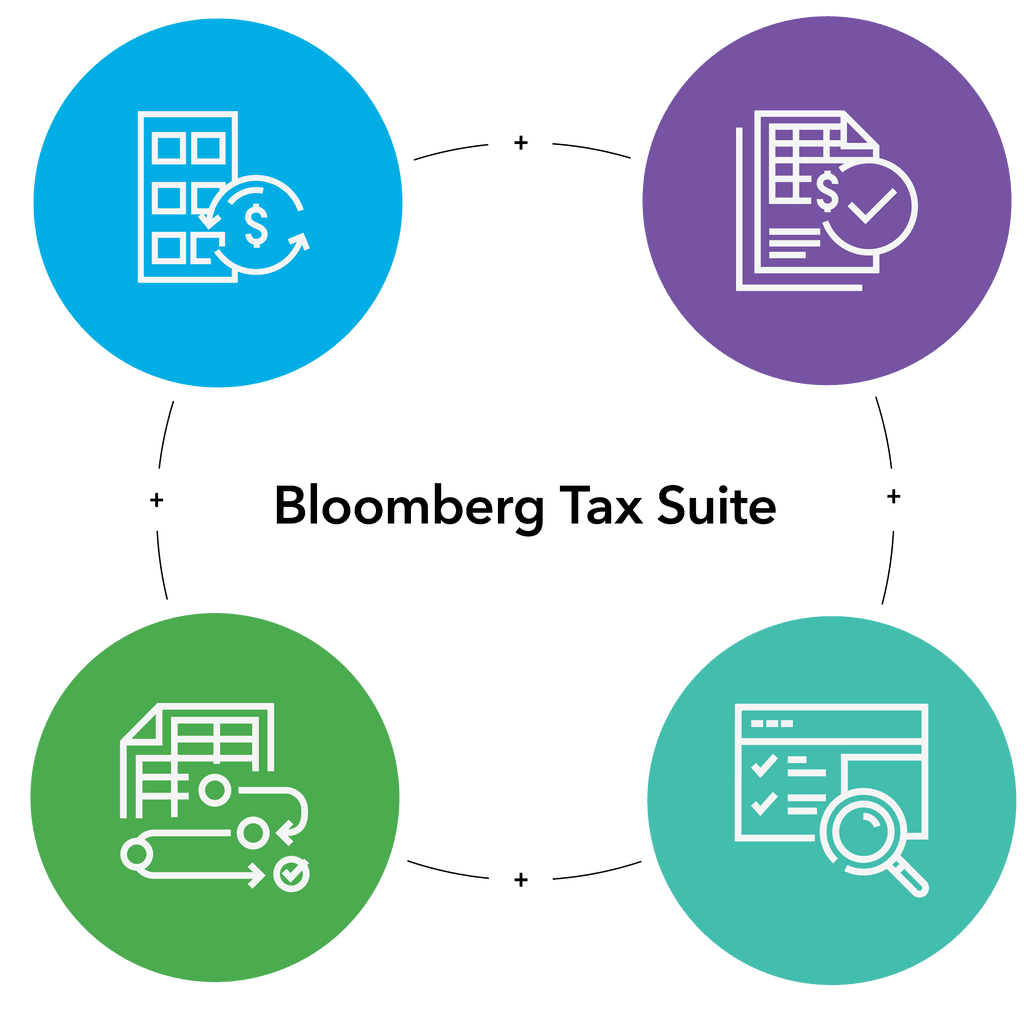

It’s time to stop wrestling with cumbersome spreadsheets and manually debugging your calculations. Meet the Bloomberg Tax suite – integrated solutions that modernize your tax process, from data collection to calculations.

To deliver the best tax strategy, you need the best tools

Today’s tax professionals deserve integrated tax tools

Tax processes are outdated, relying on clunky technology and unwieldy processes – not to mention the hours spent tracking down the latest rules and regulations. We’re here to tell you there is a better way.

Bloomberg Tax’s suite of tools was built just for you. With streamlined technology, familiar workflows, and powerful data connections, it’s like your entire workflow just entered the 21st century.

Flagship Research Platform

The gold standard of reliable and timely tax insights, delivered on an intuitive platform.

Provision Software

The most powerful ASC 740 calculation engine on the market – taking manual risks out of the equation.

Fixed Assets Software

Cloud-based asset management tool that automatically and accurately calculates depreciation.

Workpapers Software

Automatic data transformation and time-saving tax-specific functions give you complete control of your workpapers.

Transform your tax technology

Automate smarter

Reap the benefit of tax-focused automation capabilities – so you can spend your time on higher-value activities and remove risk from your process.

Integrate workflows

With tax tools that talk to each other and share data through key integrations, you can have confidence that everything from data gathering to calculations to reporting will be consistent and efficient.

Embedded Intelligence

Don’t interrupt your workflow to track down the latest rules and regs – our expert research supplies easy-to-use templates, automatically updated formulas, and AI-powered answers to save you time.

Why tax practitioners count on Bloomberg Tax

Bloomberg Tax Provision significantly reduced the time we spend on a provision. I saved close to a month over the time it used to take working in Excel.

Bloomberg Tax Fixed Assets was one of the best software decisions our company has made in recent years. We can now pull multiple companies’ information and also download asset data into a usable format. We spend less time pulling reports and entering information and more time analyzing and comparing data.

What we spend with Bloomberg Tax & Accounting Research is far less than the (cost of) daily issues that come up for which we would otherwise have to ask a law or accounting firm.

Read our latest tax insights

The Essential Guide to ASC 740

Take control of your income tax provision process with our easy-to-use guide that helps you navigate the biggest hurdles with background, details, and examples of how ASC 740 interacts with various tax laws and corporate facts.

Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act of 2024 Roadmap

Get a section-by-section summary of the tax provisions outlined in the Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act of 2024 (H.R.7024) with this report.

BNA Picks

Access the information you need faster and easier with BNA Picks, curated recommendations that link to Tax Management Portfolios, code sections, regulations and more.

Update your tax tools now

In just 30 minutes, we can show you how our integrated tax tools will slash the time you spend on manual processes with the confidence that you’re working with the best intelligence.